You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Gurus Guru Nanak Sahib (Jayanti November 28)

Re: Guru Nanak Dev ji (Parkash November 21)

Part 1 Guru Nanak (1469 - 1539)

Sri Guru Nanak Dev ji was born in 1469 in Talwandi, a village in the Sheikhupura district, 65 kms. west of Lahore. His father was a village official in the local revenue administration. As a boy, Sri Guru Nanak learnt, besides the regional languages, Persian and Arabic. He was married in 1487 and was blessed with two sons, one in 1491 and the second in 1496. In 1485 he took up, at the instance of his brother-in-law, the appointment of an official in charge of the stores of Daulat Khan Lodhi, the Muslim ruler of the area at Sultanpur. It is there that he came into contact with Mardana, a Muslim minstrel (Mirasi) who was senior in age.

By all accounts, 1496 was the year of his enlightenment when he started on his mission. His first statement after his prophetic communion with God was "There is no Hindu, nor any Mussalman." This is an announcement of supreme significance it declared not only the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, but also his clear and primary interest not in any metaphysical doctrine but only in man and his fate. It means love your neighbour as yourself. In addition, it emphasised, simultaneously the inalienable spirituo-moral combination of his message. Accompanied by Mardana, he began his missionary tours. Apart from conveying his message and rendering help to the weak, he forcefully preached, both by precept and practice, against caste distinctions ritualism, idol worship and the pseudo-religious beliefs that had no spiritual content. He chose to mix with all. He dined and lived with men of the lowest castes and classes Considering the then prevailing cultural practices and traditions, this was something socially and religiously unheard of in those days of rigid Hindu caste system sanctioned by the scriptures and the religiously approved notions of untouchability and pollution. It is a matter of great significance that at the very beginning of his mission, the Guru's first companion was a low caste Muslim. The offerings he received during his tours, were distributed among the poor. Any surplus collected was given to his hosts to maintain a common kitchen, where all could sit and eat together without any distinction of caste and status. This institution of common kitchen or langar became a major instrument of helping the poor, and a nucleus for religious gatherings of his society and of establishing the basic equality of all castes, classes and sexes.

When Guru Nanak Dev ji were 12 years old his father gave him twenty rupees and asked him to do a business, apparently to teach him business. Guru Nanak dev ji bought food for all the money and distributed among saints, and poor. When his father asked him what happened to business? He replied that he had done a "True business" at the place where Guru Nanak dev had fed the poor, this gurdwara was made and named Sacha Sauda.

Despite the hazards of travel in those times, he performed five long tours all over the country and even outside it. He visited most of the known religious places and centres of worship. At one time he preferred to dine at the place of a low caste artisan, Bhai Lallo, instead of accepting the invitation of a high caste rich landlord, Malik Bhago, because the latter lived by exploitation of the poor and the former earned his bread by the sweat of his brow. This incident has been depicted by a symbolic representation of the reason for his preference. Sri Guru Nanak pressed in one hand the co{censored} loaf of bread from Lallo's hut and in the other the food from Bhago's house. Milk gushed forth from the loaf of Lallo's and blood from the delicacies of Bhago. This prescription for honest work and living and the condemnation of exploitation, coupled with the Guru's dictum that "riches cannot be gathered without sin and evil means," have, from the very beginning, continued to be the basic moral tenet with the Sikh mystics and the Sikh society.

During his tours, he visited numerous places of Hindu and Muslim worship. He explained and exposed through his preachings the incongruities and fruitlessness of ritualistic and ascetic practices. At Hardwar, when he found people throwing Ganges water towards the sun in the east as oblations to their ancestors in heaven, he started, as a measure of correction, throwing the water towards the West, in the direction of his fields in the Punjab. When ridiculed about his folly, he replied, "If Ganges water will reach your ancestors in heaven, why should the water I throw up not reach my fields in the Punjab, which are far less distant ?"

He spent twenty five years of his life preaching from place to place. Many of his hymns were composed during this period. They represent answers to the major religious and social problems of the day and cogent responses to the situations and incidents that he came across. Some of the hymns convey dialogues with Yogis in the Punjab and elsewhere. He denounced their methods of living and their religious views. During these tours he studied other religious systems like Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Islam. At the same time, he preached the doctrines of his new religion and mission at the places and centres he visited. Since his mystic system almost completely reversed the trends, principles and practices of the then prevailing religions, he criticised and rejected virtually all the old beliefs, rituals and harmful practices existing in the country. This explains the necessity of his long and arduous tours and the variety and profusion of his hymns on all the religious, social, political and theological issues, practices and institutions of his period.

Finally, on the completion of his tours, he settled as a peasant farmer at Kartarpur, a village in the Punjab. Bhai Gurdas, the scribe of Guru Granth Sahib, was a devout and close associate of the third and the three subsequent Gurus. He was born 12 years after Guru Nanak's death and joined the Sikh mission in his very boyhood. He became the chief missionary agent of the Gurus. Because of his intimate knowledge of the Sikh society and his being a near contemporary of Sri Guru Nanak, his writings are historically authentic and reliable. He writes that at Kartarpur Guru Nanak donned the robes of a peasant and continued his ministry. He organised Sikh societies at places he visited with their meeting places called Dharamsalas. A similar society was created at Kartarpur. In the morning, Japji was sung in the congregation. In the evening Sodar and Arti were recited. The Guru cultivated his lands and also continued with his mission and preachings. His followers throughout the country were known as Nanak-panthies or Sikhs. The places where Sikh congregation and religious gatherings of his followers were held were called Dharamsalas. These were also the places for feeding the poor. Eventually, every Sikh home became a Dharamsala.

One thing is very evident. Guru Nanak had a distinct sense of his prophethood and that his mission was God-ordained. During his preachings, he himself announced. "O Lallo, as the words of the Lord come to me, so do I express them." Successors of Guru Nanak have also made similar statements indicating that they were the messengers of God. So often Guru Nanak refers to God as his Enlightener and Teacher. His statements clearly show his belief that God had commanded him to preach an entirely new religion, the central idea of which was the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, shorn of all ritualism and priestcraft. During a dialogue with the Yogis, he stated that his mission was to help everyone. He came to be called a Guru in his lifetime. In Punjabi, the word Guru means both God and an enlightener or a prophet. During his life, his disciples were formed and came to be recognised as a separate community. He was accepted as a new religious prophet. His followers adopted a separate way of greeting each other with the words Sat Kartar (God is true). Twentyfive years of his extensive preparatory tours and preachings across the length and breadth of the country clearly show his deep conviction that the people needed a new prophetic message which God had commanded him to deliver. He chose his successor and in his own life time established him as the future Guru or enlightener of the new community. This step is of the greatest significance, showing Guru Nanak s determination and declaration that the mission which he had started and the community he had created were distinct and should be continued, promoted and developed. By the formal ceremony of appointing his successor and by giving him a new name, Angad (his part or limb), he laid down the clear principle of impersonality, unity and indivisibility of Guruship. At that time he addressed Angad by saying, Between thou and me there is now no difference. In Guru Granth Sahib there is clear acceptance and proclamation of this identity of personality in the hymns of Satta-Balwand. This unity of spiritual personality of all the Gurus has a theological and mystic implication. It is also endorsed by the fact that each of the subsequent Gurus calls himself Nanak in his hymns. Never do they call themselves by their own names as was done by other Bhagats and Illyslics. That Guru Nanak attached the highest importance to his mission is also evident from his selection of the successor by a system of test, and only when he was found perfect, was Guru Angad appointed as his successor. He was comparatively a new comer to the fold, and yet he was chosen in preference to the Guru's own son, Sri Chand, who also had the reputation of being a pious person, and Baba Budha, a devout Sikh of long standing, who during his own lifetime had the distinction of ceremonially installing all subsequent Gurus.

All these facts indicate that Guru Nanak had a clear plan and vision that his mission was to be continued as an independent and distinct spiritual system on the lines laid down by him, and that, in the context of the country, there was a clear need for the organisation of such a spiritual mission and society. In his own lifetime, he distinctly determined its direction and laid the foundations of some of the new religious institutions. In addition, he created the basis for the extension and organisation of his community and religion.

The above in brief is the story of the Guru's life. We shall now note the chief features of his work, how they arose from his message and how he proceeded to develop them during his lifetime.

(1) After his enlightenment, the first words of Guru Nanak declared the brotherhood of man. This principle formed the foundation of his new spiritual gospel. It involved a fundamental doctrinal change because moral life received the sole spiritual recognition and status. This was something entirely opposed to the religious systems in vogue in the country during the time of the Guru. All those systems were, by and large, other-worldly. As against it, the Guru by his new message brought God on earth. For the first time in the country, he made a declaration that God was deeply involved and interested in the affairs of man and the world which was real and worth living in. Having taken the first step by the proclamation of his radical message, his obvious concern was to adopt further measures to implement the same.

(2)The Guru realised that in the context and climate of the country, especially because of the then existing religious systems and the prevailing prejudices, there would be resistance to his message, which, in view of his very thesis, he wanted to convey to all. He, therefore, refused to remain at Sultanpur and preach his gospel from there. Having declared the sanctity of life, his second major step was in the planning and organisation of institutions that would spread his message. As such, his twentyfive years of extensive touring can be understood only as a major organizational step. These tours were not casual. They had a triple object. He wanted to acquaint himself with all the centres and organisations of the prevalent religious systems so as to assess the forces his mission had to contend with, and to find out the institutions that he could use in the aid of his own system. Secondly, he wanted to convey his gospel at the very centres of the old systems and point out the futile and harmful nature of their methods and practices. It is for this purpose that he visited Hardwar, Kurukshetra, Banaras, Kanshi, Maya, Ceylon, Baghdad, Mecca, etc. Simultaneously, he desired to organise all his followers and set up for them local centres for their gatherings and worship. The existence of some of these far-flung centres even up-till today is a testimony to his initiative in the Organizational and the societal field. His hymns became the sole guide and the scripture for his flock and were sung at the Dharamsalas.

(3) Guru Nanak's gospel was for all men. He proclaimed their equality in all respects. In his system, the householder's life became the primary forum of religious activity. Human life was not a burden but a privilege. His was not a concession to the laity. In fact, the normal life became the medium of spiritual training and expression. The entire discipline and institutions of the Gurus can be appreciated only if one understands that, by the very logic of Guru Nanak's system, the householder's life became essential for the seeker. On reaching Kartarpur after his tours, the Guru sent for the members of his family and lived there with them for the remaining eighteen years of his life. For the same reason his followers all over the country were not recluses. They were ordinary men, living at their own homes and pursuing their normal vocations. The Guru's system involved morning and evening prayers. Congregational gatherings of the local followers were also held at their respective Dharamsalas.

(4) After he returned to Kartarpur, Guru Nanak did not rest. He straightaway took up work as a cultivator of land, without interrupting his discourses and morning and evening prayers. It is very significant that throughout the later eighteen years of his mission he continued to work as a peasant. It was a total involvement in the moral and productive life of the community. His life was a model for others to follow. Like him all his disciples were regular workers who had not given up their normal vocations Even while he was performing the important duties of organising a new religion, he nester shirked the full-time duties of a small cultivator. By his personal example he showed that the leading of a normal man's working life was fundamental to his spiritual system Even a seemingly small departure from this basic tenet would have been misunderstood and misconstrued both by his own followers and others. In the Guru's system, idleness became a vice and engagement in productive and constructive work a virtue. It was Guru Nanak who chastised ascetics as idlers and condemned their practice of begging for food at the doors of the householders.

(5) According to the Guru, moral life was the sole medium of spiritual progress In those times, caste, religious and social distinctions, and the idea of pollution were major problems. Unfortunately, these distinctions had received religious sanction The problem of poverty and food was another moral challenge. The institution of langar had a twin purpose. As every one sat and ate at the same place and shared the same food, it cut at the root of the evil of caste, class and religious distinctions. Besides, it demolished the idea of pollution of food by the mere presence of an untouchable. Secondlys it provided food to the needy. This institution of langar and pangat was started by the Guru among all his followers wherever they had been organised. It became an integral part of the moral life of the Sikhs. Considering that a large number of his followers were of low caste and poor members of society, he, from the very start, made it clear that persons who wanted to maintain caste and class distinctions had no place in his system In fact, the twin duties of sharing one's income with the poor and doing away with social distinctions were the two obligations which every Sikh had to discharge. On this score, he left no option to anyone, since he started his mission with Mardana, a low caste Muslim, as his life long companion.

(6) The greatest departure Guru Nanak made was to prescribe for the religious man the responsibility of confronting evil and oppression. It was he who said that God destroys 'the evil doers' and 'the demonical; and that such being God s nature and will, it is man's goal to carry out that will. Since there are evil doers in life, it is the spiritual duty of the seeker and his society to resist evil and injustice. Again, it is Guru Nanak who protests and complains that Babur had been committing tyranny against the weak and the innocent. Having laid the principle and the doctrine, it was again he who proceeded to organise a society. because political and societal oppression cannot be resisted by individuals, the same can be confronted only by a committed society. It was, therefore, he who proceeded to create a society and appointed a successor with the clear instructions to develop his Panth. Again, it was Guru Nanak who emphasized that life is a game of love, and once on that path one should not shirk laying down one's life. Love of one's brother or neighbour also implies, if love is true, his or her protection from attack, injustice and tyranny. Hence, the necessity of creating a religious society that can discharge this spiritual obligation. Ihis is the rationale of Guru Nanak's system and the development of the Sikh society which he organised.

(7) The Guru expressed all his teachings in Punjabi, the spoken language of Northern India. It was a clear indication of his desire not to address the elite alone but the masses as well. It is recorded that the Sikhs had no regard for Sanskrit, which was the sole scriptural language of the Hindus. Both these facts lead to important inferences. They reiterate that the Guru's message was for all. It was not for the few who, because of their personal aptitude, should feel drawn to a life of a so-called spiritual meditation and contemplation. Nor was it an exclusive spiritual system divorced from the normal life. In addition, it stressed that the Guru's message was entirely new and was completely embodied in his hymns. His disciples used his hymns as their sole guide for all their moral, religious and spiritual purposes. I hirdly, the disregard of the Sikhs for Sanskrit strongly suggests that not only was the Guru's message independent and self-contained, without reference and resort to the Sanskrit scriptures and literature, but also that the Guru made a deliberate attempt to cut off his disciples completely from all the traditional sources and the priestly class. Otherwise, the old concepts, ritualistic practices, modes of worship and orthodox religions were bound to affect adversely the growth of his religion which had wholly a different basis and direction and demanded an entirely new approach. The following hymn from Guru Nanak and the subsequent one from Sankara are contrast in their approach to the world.

"the sun and moon, O Lord, are Thy lamps; the firmament Thy salver; the orbs of the stars the pearls encased in it.

The perfume of the sandal is Thine incense, the wind is Thy fan, all the forests are Thy flowers, O Lord of light.

What worship is this, O Thou destroyer of birth ? Unbeaten strains of ecstasy are the trumpets of Thy worship.

Thou has a thousand eyes and yet not one eye; Thou host a thousand forms and yet not one form;

Thou hast a thousand stainless feet and yet not one foot; Thou hast a thousand organs of smell and yet not one organ. I am fascinated by this play of 'l hine.

The light which is in everything is Chine, O Lord of light.

From its brilliancy everything is illuminated;

By the Guru's teaching the light becometh manifest.

What pleaseth Thee is the real worship.

O God, my mind is fascinated with Thy lotus feet as the bumble-bee with the flower; night and day I thirst for them.

Give the water of Thy favour to the Sarang (bird) Nanak, so that he may dwell in Thy Name."3

http://www.sikh-history.com/sikhhist/gurus/nanak1.html

Part 1 Guru Nanak (1469 - 1539)

Sri Guru Nanak Dev ji was born in 1469 in Talwandi, a village in the Sheikhupura district, 65 kms. west of Lahore. His father was a village official in the local revenue administration. As a boy, Sri Guru Nanak learnt, besides the regional languages, Persian and Arabic. He was married in 1487 and was blessed with two sons, one in 1491 and the second in 1496. In 1485 he took up, at the instance of his brother-in-law, the appointment of an official in charge of the stores of Daulat Khan Lodhi, the Muslim ruler of the area at Sultanpur. It is there that he came into contact with Mardana, a Muslim minstrel (Mirasi) who was senior in age.

By all accounts, 1496 was the year of his enlightenment when he started on his mission. His first statement after his prophetic communion with God was "There is no Hindu, nor any Mussalman." This is an announcement of supreme significance it declared not only the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, but also his clear and primary interest not in any metaphysical doctrine but only in man and his fate. It means love your neighbour as yourself. In addition, it emphasised, simultaneously the inalienable spirituo-moral combination of his message. Accompanied by Mardana, he began his missionary tours. Apart from conveying his message and rendering help to the weak, he forcefully preached, both by precept and practice, against caste distinctions ritualism, idol worship and the pseudo-religious beliefs that had no spiritual content. He chose to mix with all. He dined and lived with men of the lowest castes and classes Considering the then prevailing cultural practices and traditions, this was something socially and religiously unheard of in those days of rigid Hindu caste system sanctioned by the scriptures and the religiously approved notions of untouchability and pollution. It is a matter of great significance that at the very beginning of his mission, the Guru's first companion was a low caste Muslim. The offerings he received during his tours, were distributed among the poor. Any surplus collected was given to his hosts to maintain a common kitchen, where all could sit and eat together without any distinction of caste and status. This institution of common kitchen or langar became a major instrument of helping the poor, and a nucleus for religious gatherings of his society and of establishing the basic equality of all castes, classes and sexes.

When Guru Nanak Dev ji were 12 years old his father gave him twenty rupees and asked him to do a business, apparently to teach him business. Guru Nanak dev ji bought food for all the money and distributed among saints, and poor. When his father asked him what happened to business? He replied that he had done a "True business" at the place where Guru Nanak dev had fed the poor, this gurdwara was made and named Sacha Sauda.

Despite the hazards of travel in those times, he performed five long tours all over the country and even outside it. He visited most of the known religious places and centres of worship. At one time he preferred to dine at the place of a low caste artisan, Bhai Lallo, instead of accepting the invitation of a high caste rich landlord, Malik Bhago, because the latter lived by exploitation of the poor and the former earned his bread by the sweat of his brow. This incident has been depicted by a symbolic representation of the reason for his preference. Sri Guru Nanak pressed in one hand the co{censored} loaf of bread from Lallo's hut and in the other the food from Bhago's house. Milk gushed forth from the loaf of Lallo's and blood from the delicacies of Bhago. This prescription for honest work and living and the condemnation of exploitation, coupled with the Guru's dictum that "riches cannot be gathered without sin and evil means," have, from the very beginning, continued to be the basic moral tenet with the Sikh mystics and the Sikh society.

During his tours, he visited numerous places of Hindu and Muslim worship. He explained and exposed through his preachings the incongruities and fruitlessness of ritualistic and ascetic practices. At Hardwar, when he found people throwing Ganges water towards the sun in the east as oblations to their ancestors in heaven, he started, as a measure of correction, throwing the water towards the West, in the direction of his fields in the Punjab. When ridiculed about his folly, he replied, "If Ganges water will reach your ancestors in heaven, why should the water I throw up not reach my fields in the Punjab, which are far less distant ?"

He spent twenty five years of his life preaching from place to place. Many of his hymns were composed during this period. They represent answers to the major religious and social problems of the day and cogent responses to the situations and incidents that he came across. Some of the hymns convey dialogues with Yogis in the Punjab and elsewhere. He denounced their methods of living and their religious views. During these tours he studied other religious systems like Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Islam. At the same time, he preached the doctrines of his new religion and mission at the places and centres he visited. Since his mystic system almost completely reversed the trends, principles and practices of the then prevailing religions, he criticised and rejected virtually all the old beliefs, rituals and harmful practices existing in the country. This explains the necessity of his long and arduous tours and the variety and profusion of his hymns on all the religious, social, political and theological issues, practices and institutions of his period.

Finally, on the completion of his tours, he settled as a peasant farmer at Kartarpur, a village in the Punjab. Bhai Gurdas, the scribe of Guru Granth Sahib, was a devout and close associate of the third and the three subsequent Gurus. He was born 12 years after Guru Nanak's death and joined the Sikh mission in his very boyhood. He became the chief missionary agent of the Gurus. Because of his intimate knowledge of the Sikh society and his being a near contemporary of Sri Guru Nanak, his writings are historically authentic and reliable. He writes that at Kartarpur Guru Nanak donned the robes of a peasant and continued his ministry. He organised Sikh societies at places he visited with their meeting places called Dharamsalas. A similar society was created at Kartarpur. In the morning, Japji was sung in the congregation. In the evening Sodar and Arti were recited. The Guru cultivated his lands and also continued with his mission and preachings. His followers throughout the country were known as Nanak-panthies or Sikhs. The places where Sikh congregation and religious gatherings of his followers were held were called Dharamsalas. These were also the places for feeding the poor. Eventually, every Sikh home became a Dharamsala.

One thing is very evident. Guru Nanak had a distinct sense of his prophethood and that his mission was God-ordained. During his preachings, he himself announced. "O Lallo, as the words of the Lord come to me, so do I express them." Successors of Guru Nanak have also made similar statements indicating that they were the messengers of God. So often Guru Nanak refers to God as his Enlightener and Teacher. His statements clearly show his belief that God had commanded him to preach an entirely new religion, the central idea of which was the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, shorn of all ritualism and priestcraft. During a dialogue with the Yogis, he stated that his mission was to help everyone. He came to be called a Guru in his lifetime. In Punjabi, the word Guru means both God and an enlightener or a prophet. During his life, his disciples were formed and came to be recognised as a separate community. He was accepted as a new religious prophet. His followers adopted a separate way of greeting each other with the words Sat Kartar (God is true). Twentyfive years of his extensive preparatory tours and preachings across the length and breadth of the country clearly show his deep conviction that the people needed a new prophetic message which God had commanded him to deliver. He chose his successor and in his own life time established him as the future Guru or enlightener of the new community. This step is of the greatest significance, showing Guru Nanak s determination and declaration that the mission which he had started and the community he had created were distinct and should be continued, promoted and developed. By the formal ceremony of appointing his successor and by giving him a new name, Angad (his part or limb), he laid down the clear principle of impersonality, unity and indivisibility of Guruship. At that time he addressed Angad by saying, Between thou and me there is now no difference. In Guru Granth Sahib there is clear acceptance and proclamation of this identity of personality in the hymns of Satta-Balwand. This unity of spiritual personality of all the Gurus has a theological and mystic implication. It is also endorsed by the fact that each of the subsequent Gurus calls himself Nanak in his hymns. Never do they call themselves by their own names as was done by other Bhagats and Illyslics. That Guru Nanak attached the highest importance to his mission is also evident from his selection of the successor by a system of test, and only when he was found perfect, was Guru Angad appointed as his successor. He was comparatively a new comer to the fold, and yet he was chosen in preference to the Guru's own son, Sri Chand, who also had the reputation of being a pious person, and Baba Budha, a devout Sikh of long standing, who during his own lifetime had the distinction of ceremonially installing all subsequent Gurus.

All these facts indicate that Guru Nanak had a clear plan and vision that his mission was to be continued as an independent and distinct spiritual system on the lines laid down by him, and that, in the context of the country, there was a clear need for the organisation of such a spiritual mission and society. In his own lifetime, he distinctly determined its direction and laid the foundations of some of the new religious institutions. In addition, he created the basis for the extension and organisation of his community and religion.

The above in brief is the story of the Guru's life. We shall now note the chief features of his work, how they arose from his message and how he proceeded to develop them during his lifetime.

(1) After his enlightenment, the first words of Guru Nanak declared the brotherhood of man. This principle formed the foundation of his new spiritual gospel. It involved a fundamental doctrinal change because moral life received the sole spiritual recognition and status. This was something entirely opposed to the religious systems in vogue in the country during the time of the Guru. All those systems were, by and large, other-worldly. As against it, the Guru by his new message brought God on earth. For the first time in the country, he made a declaration that God was deeply involved and interested in the affairs of man and the world which was real and worth living in. Having taken the first step by the proclamation of his radical message, his obvious concern was to adopt further measures to implement the same.

(2)The Guru realised that in the context and climate of the country, especially because of the then existing religious systems and the prevailing prejudices, there would be resistance to his message, which, in view of his very thesis, he wanted to convey to all. He, therefore, refused to remain at Sultanpur and preach his gospel from there. Having declared the sanctity of life, his second major step was in the planning and organisation of institutions that would spread his message. As such, his twentyfive years of extensive touring can be understood only as a major organizational step. These tours were not casual. They had a triple object. He wanted to acquaint himself with all the centres and organisations of the prevalent religious systems so as to assess the forces his mission had to contend with, and to find out the institutions that he could use in the aid of his own system. Secondly, he wanted to convey his gospel at the very centres of the old systems and point out the futile and harmful nature of their methods and practices. It is for this purpose that he visited Hardwar, Kurukshetra, Banaras, Kanshi, Maya, Ceylon, Baghdad, Mecca, etc. Simultaneously, he desired to organise all his followers and set up for them local centres for their gatherings and worship. The existence of some of these far-flung centres even up-till today is a testimony to his initiative in the Organizational and the societal field. His hymns became the sole guide and the scripture for his flock and were sung at the Dharamsalas.

(3) Guru Nanak's gospel was for all men. He proclaimed their equality in all respects. In his system, the householder's life became the primary forum of religious activity. Human life was not a burden but a privilege. His was not a concession to the laity. In fact, the normal life became the medium of spiritual training and expression. The entire discipline and institutions of the Gurus can be appreciated only if one understands that, by the very logic of Guru Nanak's system, the householder's life became essential for the seeker. On reaching Kartarpur after his tours, the Guru sent for the members of his family and lived there with them for the remaining eighteen years of his life. For the same reason his followers all over the country were not recluses. They were ordinary men, living at their own homes and pursuing their normal vocations. The Guru's system involved morning and evening prayers. Congregational gatherings of the local followers were also held at their respective Dharamsalas.

(4) After he returned to Kartarpur, Guru Nanak did not rest. He straightaway took up work as a cultivator of land, without interrupting his discourses and morning and evening prayers. It is very significant that throughout the later eighteen years of his mission he continued to work as a peasant. It was a total involvement in the moral and productive life of the community. His life was a model for others to follow. Like him all his disciples were regular workers who had not given up their normal vocations Even while he was performing the important duties of organising a new religion, he nester shirked the full-time duties of a small cultivator. By his personal example he showed that the leading of a normal man's working life was fundamental to his spiritual system Even a seemingly small departure from this basic tenet would have been misunderstood and misconstrued both by his own followers and others. In the Guru's system, idleness became a vice and engagement in productive and constructive work a virtue. It was Guru Nanak who chastised ascetics as idlers and condemned their practice of begging for food at the doors of the householders.

(5) According to the Guru, moral life was the sole medium of spiritual progress In those times, caste, religious and social distinctions, and the idea of pollution were major problems. Unfortunately, these distinctions had received religious sanction The problem of poverty and food was another moral challenge. The institution of langar had a twin purpose. As every one sat and ate at the same place and shared the same food, it cut at the root of the evil of caste, class and religious distinctions. Besides, it demolished the idea of pollution of food by the mere presence of an untouchable. Secondlys it provided food to the needy. This institution of langar and pangat was started by the Guru among all his followers wherever they had been organised. It became an integral part of the moral life of the Sikhs. Considering that a large number of his followers were of low caste and poor members of society, he, from the very start, made it clear that persons who wanted to maintain caste and class distinctions had no place in his system In fact, the twin duties of sharing one's income with the poor and doing away with social distinctions were the two obligations which every Sikh had to discharge. On this score, he left no option to anyone, since he started his mission with Mardana, a low caste Muslim, as his life long companion.

(6) The greatest departure Guru Nanak made was to prescribe for the religious man the responsibility of confronting evil and oppression. It was he who said that God destroys 'the evil doers' and 'the demonical; and that such being God s nature and will, it is man's goal to carry out that will. Since there are evil doers in life, it is the spiritual duty of the seeker and his society to resist evil and injustice. Again, it is Guru Nanak who protests and complains that Babur had been committing tyranny against the weak and the innocent. Having laid the principle and the doctrine, it was again he who proceeded to organise a society. because political and societal oppression cannot be resisted by individuals, the same can be confronted only by a committed society. It was, therefore, he who proceeded to create a society and appointed a successor with the clear instructions to develop his Panth. Again, it was Guru Nanak who emphasized that life is a game of love, and once on that path one should not shirk laying down one's life. Love of one's brother or neighbour also implies, if love is true, his or her protection from attack, injustice and tyranny. Hence, the necessity of creating a religious society that can discharge this spiritual obligation. Ihis is the rationale of Guru Nanak's system and the development of the Sikh society which he organised.

(7) The Guru expressed all his teachings in Punjabi, the spoken language of Northern India. It was a clear indication of his desire not to address the elite alone but the masses as well. It is recorded that the Sikhs had no regard for Sanskrit, which was the sole scriptural language of the Hindus. Both these facts lead to important inferences. They reiterate that the Guru's message was for all. It was not for the few who, because of their personal aptitude, should feel drawn to a life of a so-called spiritual meditation and contemplation. Nor was it an exclusive spiritual system divorced from the normal life. In addition, it stressed that the Guru's message was entirely new and was completely embodied in his hymns. His disciples used his hymns as their sole guide for all their moral, religious and spiritual purposes. I hirdly, the disregard of the Sikhs for Sanskrit strongly suggests that not only was the Guru's message independent and self-contained, without reference and resort to the Sanskrit scriptures and literature, but also that the Guru made a deliberate attempt to cut off his disciples completely from all the traditional sources and the priestly class. Otherwise, the old concepts, ritualistic practices, modes of worship and orthodox religions were bound to affect adversely the growth of his religion which had wholly a different basis and direction and demanded an entirely new approach. The following hymn from Guru Nanak and the subsequent one from Sankara are contrast in their approach to the world.

"the sun and moon, O Lord, are Thy lamps; the firmament Thy salver; the orbs of the stars the pearls encased in it.

The perfume of the sandal is Thine incense, the wind is Thy fan, all the forests are Thy flowers, O Lord of light.

What worship is this, O Thou destroyer of birth ? Unbeaten strains of ecstasy are the trumpets of Thy worship.

Thou has a thousand eyes and yet not one eye; Thou host a thousand forms and yet not one form;

Thou hast a thousand stainless feet and yet not one foot; Thou hast a thousand organs of smell and yet not one organ. I am fascinated by this play of 'l hine.

The light which is in everything is Chine, O Lord of light.

From its brilliancy everything is illuminated;

By the Guru's teaching the light becometh manifest.

What pleaseth Thee is the real worship.

O God, my mind is fascinated with Thy lotus feet as the bumble-bee with the flower; night and day I thirst for them.

Give the water of Thy favour to the Sarang (bird) Nanak, so that he may dwell in Thy Name."3

http://www.sikh-history.com/sikhhist/gurus/nanak1.html

Re: Guru Nanak Dev ji (Parkash November 21)

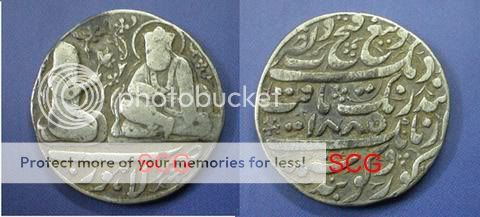

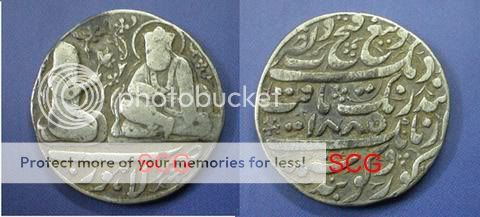

It Is A North Indian Coin from region of PUNJAB and depicts the Sikh faith. A rare coin purportedly minted 260 years ago in 1748 by one of the Sikh missals. (Minted 1804 is Hindu calendar call Vikram Smavat started 56 years ahead of Georgian Calendar) The coin made of an alloy resembling bronze, bears picture of the first Guru (Shri Guru Nanak Dev Ji) on observe (Date Side) exergues reads Sant Kartar and the tenth Guru (Shri Guru Govind Singh Ji) on the reverse side. While Guru Nanak Dev is flanked by Bhai Mardana and Bhai Bala, holding rabab(Violin like instrument) and chaur(Hand-held Fan) in their hands, a bai is seen sitting near Guru Gobind Singh. Also shown in the picture are the khrawon (slipper made of wood) and a lota (small water pot). It Is claimed and maintained that the ambiguity about the pictorial and mohar coins was due to lack of concern shown by successive governments about the Sikh history. It was certainly after October 14, 1745, that the chief of missals started minting coins in the names of the ten Gurus. The very fact the coin bears pictures of the first and the tenth Guru shows that it was not minted during the regime of any sovereign ruler . Referring to the pages of history, each chief tried to strengthen his hold over the areas under his control and even started minting coins. A number of mints in Amritsar and one at Anandgarh came into existence. But a special feature of these mints was that coins were minted by all in the name of the Sikh Gurus as had been the traditional practice and no chief put his name on these coins or even changed the legend.

It Is A North Indian Coin from region of PUNJAB and depicts the Sikh faith. A rare coin purportedly minted 260 years ago in 1748 by one of the Sikh missals. (Minted 1804 is Hindu calendar call Vikram Smavat started 56 years ahead of Georgian Calendar) The coin made of an alloy resembling bronze, bears picture of the first Guru (Shri Guru Nanak Dev Ji) on observe (Date Side) exergues reads Sant Kartar and the tenth Guru (Shri Guru Govind Singh Ji) on the reverse side. While Guru Nanak Dev is flanked by Bhai Mardana and Bhai Bala, holding rabab(Violin like instrument) and chaur(Hand-held Fan) in their hands, a bai is seen sitting near Guru Gobind Singh. Also shown in the picture are the khrawon (slipper made of wood) and a lota (small water pot). It Is claimed and maintained that the ambiguity about the pictorial and mohar coins was due to lack of concern shown by successive governments about the Sikh history. It was certainly after October 14, 1745, that the chief of missals started minting coins in the names of the ten Gurus. The very fact the coin bears pictures of the first and the tenth Guru shows that it was not minted during the regime of any sovereign ruler . Referring to the pages of history, each chief tried to strengthen his hold over the areas under his control and even started minting coins. A number of mints in Amritsar and one at Anandgarh came into existence. But a special feature of these mints was that coins were minted by all in the name of the Sikh Gurus as had been the traditional practice and no chief put his name on these coins or even changed the legend.

Attachments

Re: Guru Nanak Dev ji (Parkash November 21)

His travels. Maps from Sikh Archives

http://www.sikharchives.com/?p=6246

His travels. Maps from Sikh Archives

http://www.sikharchives.com/?p=6246

Attachments

Re: Guru Nanak Dev ji (Parkash November 21)

Part 2 Guru Nanak: Moral Philosopher and Householder (continued from Sikh History)

Sankara writes: "I am not a combination of the five perishable elements I arn neither body, the senses, nor what is in the body (antar-anga: i e., the mind). I am not the ego-function: I am not the group of the vital breathforces; I am not intuitive intelligence (buddhi). Far from wife and son am 1, far from land and wealth and other notions of that kind. I am the Witness, the Eternal, the Inner Self, the Blissful One (sivoham; suggesting also, 'I am Siva')."

"Owing to ignorance of the rope the rope appears to be a snake; owing to ignorance of the Self the transient state arises of the individualized, limited, phenomenal aspect of the Self. The rope becomes a rope when the false impression disappears because of the statement of some credible person; because of the statement of my teacher I am not an individual life-monad (yivo-naham), I am the Blissful One (sivo-ham )."

"I am not the born; how can there be either birth or death for me ?"

"I am not the vital air; how can there be either hunger or thirst for me ?"

"I am not the mind, the organ of thought and feeling; how can there be either sorrow or delusion for me ?"

"I am not the doer; how can there be either bondage or release for me ?"

"I am neither male nor female, nor am I sexless. I am the Peaceful One, whose form is self-effulgent, powerful radiance. I am neither a child, a young man, nor an ancient; nor am I of any caste. I do not belong to one of the four lifestages. I am the Blessed-Peaceful One, who is the only Cause of the origin and dissolution of the world."4

While Guru Nanak is bewitched by the beauty of His creation and sees in the panorama of nature a lovely scene of the worshipful adoration of the Lord, Sankara in his hymn rejects the reality of the world and treats himself as the Sole Reality. Zimmer feels that "Such holy megalomania goes past the bounds of sense. With Sankara, the grandeur of the supreme human experience becomes intellectualized and reveals its inhuman sterility."5

No wonder that Guru Nanak found the traditional religions and concepts as of no use for his purpose. He calculatedly tried to wean away his people from them. For Guru Nanak, religion did not consist in a 'patched coat or besmearing oneself with ashes"6 but in treating all as equals. For him the service of man is supreme and that alone wins a place in God's heart.

By this time it should be easy to discern that all the eight features of the Guru's system are integrally connected. In fact, one flows from the other and all follow from the basic tenet of his spiritual system, viz., the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. For Guru Nanak, life and human beings became the sole field of his work. Thus arose the spiritual necessity of a normal life and work and the identity of moral and spiritual functioning and growth.

Having accepted the primacy of moral life and its spiritual validity, the Guru proceeded to identify the chief moral problems of his time. These were caste and class distinctions, the institutions, of property and wealth, and poverty and scarcity of food. Immoral institutions could be substituted and replaced only by the setting up of rival institutions. Guru Nanak believed that while it is essential to elevate man internally, it is equally necessary to uplift the fallen and the downtrodden in actual life. Because, the ultimate test of one's spiritual progress is the kind of moral life one leads in the social field. The Guru not only accepted the necessity of affecting change in the environment, but also endeavoured to build new institutions. We shall find that these eight basic principles of the spirituo-moral life enunciated by Guru Nanak, were strictly carried out by his successors. As envisaged by the first prophet, his successors further extended the structure and organised the institutions of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak. Though we shall consider these points while dealing with the lives of the other nine Gurus, some of them need to be mentioned here.

The primacy of the householder's life was maintained. Everyone of the Gurus, excepting Guru Harkishan who died at an early age, was a married person who maintained a family. When Guru Nanak, sent Guru Angad from Kartarpur to Khadur Sahib to start his mission there, he advised him to send for the members of his family and live a normal life. According to Bhalla,8 when Guru Nanak went to visit Guru Angad at Khadur Sahib, he found him living a life of withdrawal and meditation. Guru Nanak directed him to be active as he had to fulfill his mission and organise a community inspired by his religious principles.

Work in life, both for earning the livelihood and serving the common good, continued to be the fundamental tenet of Sikhism. There is a clear record that everyone upto the Fifth Guru (and probably subsequent Gurus too) earned his livelihood by a separate vocation and contributed his surplus to the institution of langar Each Sikh was made to accept his social responsibility. So much so that Guru Angad and finally Guru Amar Das clearly ordered that Udasis, persons living a celibate and ascetic life without any productive vocation, should remain excluded from the Sikh fold. As against it, any worker or a householder without distinction of class or caste could become a Sikh. This indicates how these two principles were deemed fundamental to the mystic system of Guru Nanak. It was defined and laid down that in Sikhism a normal productive and moral life could alone be the basis of spiritual progress. Here, by the very rationale of the mystic path, no one who was not following a normal life could be fruitfully included.

The organization of moral life and institutions, of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak, came to be the chief concern of the other Gurus. We refer to the sociopolitical martyrdoms of two of the Gurus and the organisation of the military struggle by the Sixth Guru and his successors. Here it would be pertinent to mention Bhai Gurdas's narration of Guru Nanak's encounter and dialogue with the Nath Yogis who were living an ascetic life of retreat in the remote hills. They asked Guru Nanak how the world below in the plains was faring. ' How could it be well", replied Guru Nanak, "when the so- called pious men had resorted to the seclusion of the hills ?" The Naths commented that it was incongruous and self-contradictory for Guru Nanak to be a householder and also pretend to lead a spiritual life. That, they said, was like putting acid in milk and thereby destroying its purity. The Guru replied emphatically that the Naths were ignorant of even the basic elements of spiritual life.9 This authentic record of the dialouge reveals the then prevailing religious thought in the country. It points to the clear and deliberate break the Guru made from the traditional system.

While Guru Nanak was catholic in his criticism of other religions, he was unsparing where he felt it necessary to clarify an issue or to keep his flock away from a wrong practice or prejudice. He categorically attacked all the evil institutions of his time including oppression and barbarity in the political field, corruption among the officialss and hypocrisy and greed in the priestly class. He deprecated the degrading practices of inequality in the social field. He criticised and repudiated the scriptures that sanctioned such practices. After having denounced all of them, he took tangible steps to create a society that accepted the religious responsibility of eliminating these evils from the new institutions created by him and of attacking the evil practices and institutions in the Social and political fields. T his was a fundamental institutional change with the largest dimensions and implications for the future of the community and the country. The very fact that originally poorer classes were attracted to the Gurus, fold shows that they found there a society and a place where they could breathe freely and live with a sense of equality and dignity.

Dr H.R. Gupta, the well-known historian, writes, "Nanak's religion consisted in the love of God, love of man and love of godly living. His religion was above the limits of caste, creed and country. He gave his love to all, Hindus, Muslims, Indians and foreigners alike. His religion was a people's movement based on modern conceptions of secularism and socialism, a common brotherhood of all human beings. Like Rousseau, Nanak felt 250 years earlier that it was the common people who made up the human race Ihey had always toiled and tussled for princes, priests and politicians. What did not concern the common people was hardly worth considering. Nanak's work to begin with assumed the form of an agrarian movement. His teachings were purely in Puniabi language mostly spoken by cultivators. Obey appealed to the downtrodden and the oppressed peasants and petty traders as they were ground down between the two mill stones of Government tyranny and the new Muslims' brutality. Nanak's faith was simple and sublime. It was the life lived. His religion was not a system of philosophy like Hinduism. It was a discipline, a way of life, a force, which connected one Sikh with another as well as with the Guru."'° "In Nanak s time Indian society was based on caste and was divided into countless watertight Compartments. Men were considered high and low on account of their birth and not according to their deeds. Equality of human beings was a dream. There was no spirit of national unity except feelings of community fellowship. In Nanak's views men's love of God was the criterion to judge whether a person was good or bad, high or low. As the caste system was not based on divine love, he condemned it. Nanak aimed at creating a casteless and classless society similar to the modern type of socialist society in which all were equal and where one member did not exploit the other. Nanak insisted that every Sikh house should serve as a place of love and devotion, a true guest house (Sach dharamshala). Every Sikh was enjoined to welcome a traveller or a needy person and to share his meals and other comforts with him. "Guru Nanak aimed at uplifting the individual as well as building a nation."

Considering the religious conditions and the philosophies of the time and the social and political milieu in which Guru Nanak was born, the new spirituo- moral thesis he introduced and the changes he brought about in the social and spiritual field were indeed radical and revolutionary. Earlier, release from the bondage of the world was sought as the goal. The householder's life was considered an impediment and an entanglement to be avoided by seclusion, monasticism, celibacy, sanyasa or vanpraslha. In contrast, in the Guru's system the world became the arena of spiritual endeavour. A normal life and moral and righteous deeds became the fundamental means of spiritual progress, since these alone were approved by God. Man was free to choose between the good and the bad and shape his own future by choosing virtue and fighting evil. All this gave "new hope, new faith, new life and new expectations to the depressed, dejected and downcast people of Punjab."

Guru Nanak's religious concepts and system were entirely opposed to those of the traditional religions in the country. His views were different even from those of the saints of the Radical Bhakti movement. From the very beginning of his mission, he started implementing his doctrines and creating institutions for their practice and development. In his time the religious energy and zeal were flowing away from the empirical world into the desert of otherworldliness, asceticism and renunciation. It was Guru Nanak's mission and achievement not only to dam that Amazon of moral and spiritual energy but also to divert it into the world so as to enrich the moral, social the political life of man. We wonder if, in the context of his times, anything could be more astounding and miraculous. The task was undertaken with a faith, confidence and determination which could only be prophetic.

It is indeed the emphatic manifestation of his spiritual system into the moral formations and institutions that created a casteless society of people who mixed freely, worked and earned righteously, contributed some of their income to the common causes and the langar. It was this community, with all kinds of its shackles broken and a new freedom gained, that bound its members with a new sense of cohesion, enabling it to rise triumphant even though subjected to the severest of political and military persecutions.

The life of Guru Nanak shows that the only interpretation of his thesis and doctrines could be the one which we have accepted. He expressed his doctrines through the medium of activities. He himself laid the firm foundations of institutions and trends which flowered and fructified later on. As we do not find a trace of those ideas and institutions in the religious milieu of his time or the religious history of the country, the entirely original and new character of his spiritual system could have only been mystically and prophetically inspired.

Apart from the continuation, consolidation and expansion of Guru Nanak's mission, the account that follows seeks to present the major contributions made by the remaining Gurus.

Part 2 Guru Nanak: Moral Philosopher and Householder (continued from Sikh History)

Sankara writes: "I am not a combination of the five perishable elements I arn neither body, the senses, nor what is in the body (antar-anga: i e., the mind). I am not the ego-function: I am not the group of the vital breathforces; I am not intuitive intelligence (buddhi). Far from wife and son am 1, far from land and wealth and other notions of that kind. I am the Witness, the Eternal, the Inner Self, the Blissful One (sivoham; suggesting also, 'I am Siva')."

"Owing to ignorance of the rope the rope appears to be a snake; owing to ignorance of the Self the transient state arises of the individualized, limited, phenomenal aspect of the Self. The rope becomes a rope when the false impression disappears because of the statement of some credible person; because of the statement of my teacher I am not an individual life-monad (yivo-naham), I am the Blissful One (sivo-ham )."

"I am not the born; how can there be either birth or death for me ?"

"I am not the vital air; how can there be either hunger or thirst for me ?"

"I am not the mind, the organ of thought and feeling; how can there be either sorrow or delusion for me ?"

"I am not the doer; how can there be either bondage or release for me ?"

"I am neither male nor female, nor am I sexless. I am the Peaceful One, whose form is self-effulgent, powerful radiance. I am neither a child, a young man, nor an ancient; nor am I of any caste. I do not belong to one of the four lifestages. I am the Blessed-Peaceful One, who is the only Cause of the origin and dissolution of the world."4

While Guru Nanak is bewitched by the beauty of His creation and sees in the panorama of nature a lovely scene of the worshipful adoration of the Lord, Sankara in his hymn rejects the reality of the world and treats himself as the Sole Reality. Zimmer feels that "Such holy megalomania goes past the bounds of sense. With Sankara, the grandeur of the supreme human experience becomes intellectualized and reveals its inhuman sterility."5

No wonder that Guru Nanak found the traditional religions and concepts as of no use for his purpose. He calculatedly tried to wean away his people from them. For Guru Nanak, religion did not consist in a 'patched coat or besmearing oneself with ashes"6 but in treating all as equals. For him the service of man is supreme and that alone wins a place in God's heart.

By this time it should be easy to discern that all the eight features of the Guru's system are integrally connected. In fact, one flows from the other and all follow from the basic tenet of his spiritual system, viz., the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. For Guru Nanak, life and human beings became the sole field of his work. Thus arose the spiritual necessity of a normal life and work and the identity of moral and spiritual functioning and growth.

Having accepted the primacy of moral life and its spiritual validity, the Guru proceeded to identify the chief moral problems of his time. These were caste and class distinctions, the institutions, of property and wealth, and poverty and scarcity of food. Immoral institutions could be substituted and replaced only by the setting up of rival institutions. Guru Nanak believed that while it is essential to elevate man internally, it is equally necessary to uplift the fallen and the downtrodden in actual life. Because, the ultimate test of one's spiritual progress is the kind of moral life one leads in the social field. The Guru not only accepted the necessity of affecting change in the environment, but also endeavoured to build new institutions. We shall find that these eight basic principles of the spirituo-moral life enunciated by Guru Nanak, were strictly carried out by his successors. As envisaged by the first prophet, his successors further extended the structure and organised the institutions of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak. Though we shall consider these points while dealing with the lives of the other nine Gurus, some of them need to be mentioned here.

The primacy of the householder's life was maintained. Everyone of the Gurus, excepting Guru Harkishan who died at an early age, was a married person who maintained a family. When Guru Nanak, sent Guru Angad from Kartarpur to Khadur Sahib to start his mission there, he advised him to send for the members of his family and live a normal life. According to Bhalla,8 when Guru Nanak went to visit Guru Angad at Khadur Sahib, he found him living a life of withdrawal and meditation. Guru Nanak directed him to be active as he had to fulfill his mission and organise a community inspired by his religious principles.

Work in life, both for earning the livelihood and serving the common good, continued to be the fundamental tenet of Sikhism. There is a clear record that everyone upto the Fifth Guru (and probably subsequent Gurus too) earned his livelihood by a separate vocation and contributed his surplus to the institution of langar Each Sikh was made to accept his social responsibility. So much so that Guru Angad and finally Guru Amar Das clearly ordered that Udasis, persons living a celibate and ascetic life without any productive vocation, should remain excluded from the Sikh fold. As against it, any worker or a householder without distinction of class or caste could become a Sikh. This indicates how these two principles were deemed fundamental to the mystic system of Guru Nanak. It was defined and laid down that in Sikhism a normal productive and moral life could alone be the basis of spiritual progress. Here, by the very rationale of the mystic path, no one who was not following a normal life could be fruitfully included.

The organization of moral life and institutions, of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak, came to be the chief concern of the other Gurus. We refer to the sociopolitical martyrdoms of two of the Gurus and the organisation of the military struggle by the Sixth Guru and his successors. Here it would be pertinent to mention Bhai Gurdas's narration of Guru Nanak's encounter and dialogue with the Nath Yogis who were living an ascetic life of retreat in the remote hills. They asked Guru Nanak how the world below in the plains was faring. ' How could it be well", replied Guru Nanak, "when the so- called pious men had resorted to the seclusion of the hills ?" The Naths commented that it was incongruous and self-contradictory for Guru Nanak to be a householder and also pretend to lead a spiritual life. That, they said, was like putting acid in milk and thereby destroying its purity. The Guru replied emphatically that the Naths were ignorant of even the basic elements of spiritual life.9 This authentic record of the dialouge reveals the then prevailing religious thought in the country. It points to the clear and deliberate break the Guru made from the traditional system.

While Guru Nanak was catholic in his criticism of other religions, he was unsparing where he felt it necessary to clarify an issue or to keep his flock away from a wrong practice or prejudice. He categorically attacked all the evil institutions of his time including oppression and barbarity in the political field, corruption among the officialss and hypocrisy and greed in the priestly class. He deprecated the degrading practices of inequality in the social field. He criticised and repudiated the scriptures that sanctioned such practices. After having denounced all of them, he took tangible steps to create a society that accepted the religious responsibility of eliminating these evils from the new institutions created by him and of attacking the evil practices and institutions in the Social and political fields. T his was a fundamental institutional change with the largest dimensions and implications for the future of the community and the country. The very fact that originally poorer classes were attracted to the Gurus, fold shows that they found there a society and a place where they could breathe freely and live with a sense of equality and dignity.

Dr H.R. Gupta, the well-known historian, writes, "Nanak's religion consisted in the love of God, love of man and love of godly living. His religion was above the limits of caste, creed and country. He gave his love to all, Hindus, Muslims, Indians and foreigners alike. His religion was a people's movement based on modern conceptions of secularism and socialism, a common brotherhood of all human beings. Like Rousseau, Nanak felt 250 years earlier that it was the common people who made up the human race Ihey had always toiled and tussled for princes, priests and politicians. What did not concern the common people was hardly worth considering. Nanak's work to begin with assumed the form of an agrarian movement. His teachings were purely in Puniabi language mostly spoken by cultivators. Obey appealed to the downtrodden and the oppressed peasants and petty traders as they were ground down between the two mill stones of Government tyranny and the new Muslims' brutality. Nanak's faith was simple and sublime. It was the life lived. His religion was not a system of philosophy like Hinduism. It was a discipline, a way of life, a force, which connected one Sikh with another as well as with the Guru."'° "In Nanak s time Indian society was based on caste and was divided into countless watertight Compartments. Men were considered high and low on account of their birth and not according to their deeds. Equality of human beings was a dream. There was no spirit of national unity except feelings of community fellowship. In Nanak's views men's love of God was the criterion to judge whether a person was good or bad, high or low. As the caste system was not based on divine love, he condemned it. Nanak aimed at creating a casteless and classless society similar to the modern type of socialist society in which all were equal and where one member did not exploit the other. Nanak insisted that every Sikh house should serve as a place of love and devotion, a true guest house (Sach dharamshala). Every Sikh was enjoined to welcome a traveller or a needy person and to share his meals and other comforts with him. "Guru Nanak aimed at uplifting the individual as well as building a nation."

Considering the religious conditions and the philosophies of the time and the social and political milieu in which Guru Nanak was born, the new spirituo- moral thesis he introduced and the changes he brought about in the social and spiritual field were indeed radical and revolutionary. Earlier, release from the bondage of the world was sought as the goal. The householder's life was considered an impediment and an entanglement to be avoided by seclusion, monasticism, celibacy, sanyasa or vanpraslha. In contrast, in the Guru's system the world became the arena of spiritual endeavour. A normal life and moral and righteous deeds became the fundamental means of spiritual progress, since these alone were approved by God. Man was free to choose between the good and the bad and shape his own future by choosing virtue and fighting evil. All this gave "new hope, new faith, new life and new expectations to the depressed, dejected and downcast people of Punjab."

Guru Nanak's religious concepts and system were entirely opposed to those of the traditional religions in the country. His views were different even from those of the saints of the Radical Bhakti movement. From the very beginning of his mission, he started implementing his doctrines and creating institutions for their practice and development. In his time the religious energy and zeal were flowing away from the empirical world into the desert of otherworldliness, asceticism and renunciation. It was Guru Nanak's mission and achievement not only to dam that Amazon of moral and spiritual energy but also to divert it into the world so as to enrich the moral, social the political life of man. We wonder if, in the context of his times, anything could be more astounding and miraculous. The task was undertaken with a faith, confidence and determination which could only be prophetic.

It is indeed the emphatic manifestation of his spiritual system into the moral formations and institutions that created a casteless society of people who mixed freely, worked and earned righteously, contributed some of their income to the common causes and the langar. It was this community, with all kinds of its shackles broken and a new freedom gained, that bound its members with a new sense of cohesion, enabling it to rise triumphant even though subjected to the severest of political and military persecutions.

The life of Guru Nanak shows that the only interpretation of his thesis and doctrines could be the one which we have accepted. He expressed his doctrines through the medium of activities. He himself laid the firm foundations of institutions and trends which flowered and fructified later on. As we do not find a trace of those ideas and institutions in the religious milieu of his time or the religious history of the country, the entirely original and new character of his spiritual system could have only been mystically and prophetically inspired.

Apart from the continuation, consolidation and expansion of Guru Nanak's mission, the account that follows seeks to present the major contributions made by the remaining Gurus.

Guru Nanak's Concept of Nature

by Sirdar Kapur Singh

Guru Nanak was a prophet of religion and philosophy was not central to his teachings: Numerous dogmas there are and as many more intellectual disciplines. As many are the systems of philosophy. All these, so many of them are the chains that curb the spontanity of the psyche. For a man of religion, the central concern is that of liberation.1

However, Guru Nanak was not unconcerned with the study of humanities and sciences.

There are those who are cultured neither in philosophy nor in scripture nor have developed proper taste for music. And, likewise, there are those who are unaquainted with aesthetics and the arts. They have neither a trained character, nor disciplined intellect, and, as such, they are devoid of true learning, so much so that the true significance of accumulated human wisdom is outside their sphere of interest. Such people, says Nanak, are true animals for they strut as human beings without the qualifications of a human being.2

And,

Intellectual curiousity and scientific knowledge are necessary for removing doubts that beset human understanding.3

From this the following can be inferred:

i. intellectual activity is not directly relevant to religious activity.

ii. that, for a properly developed and integrated person, intellectual and scientific studies are imperative.

iii. that, although religion is philosophically indeterminate, philosophical enquiries are necessary for preparing the mind suitably towards the acceptance of religious discipline.

There are two fundamental concepts that run through almost all schools of Indian philosophy: the concept of purusa and prakriti. Broadly speaking, these concepts correspond to the concepts of 'subject' and 'object'. This duality between 'life' and 'nature' and 'mind' and 'matter' is present in the philosophies of both East and West.

Samkhya doctrines of purusa and prakriti have undergone developments over the centuries. In the Bhagavad-Gita the meanings of these concepts have been extended, whereas Vijnanabhiksu and Aniruddha have developed the classical Samkhya still further.

Noting the dualism in these philosophies, Guru Nanak has abandoned the term prakriti while retaining the term purusa. It should be noted though that the Guru's definition of purusa is different from that of the Indian philosophy as found in the classical Samkhya or the Samkhya of the Bhagvad-Gita or the Neo-Samkhya of Aniruddha and Vijnanabhikshu. For the other term of dualism Guru Nanak has employed the Arabic word qudret and has relegated prakriti altogether to other contexts.

The world, manifest or un-manifest, according to Samkhya, is not derived from the purusa ie the Nature, does not have its matrix, in the Mind. The world is comprehended in the term of purusa, but does not originate from it neither is it grounded in it. This purusa is not personal though it is discreet and individual (Karika, 38).4 It is the propinquity of this purusa, to prakriti which gives rise to the world of appearances. In the absence of this nearness, the world is there but it simply remains avyakta, un-manifest. 'The world is that which is perceived or witnessed, lokyanti iti lokah, and thus the world of appearances serves the purpose of the individual purusa, purusartha.(Karika, 63).5

This discrete and individual purusa is in itself translucent and transparent; it is a witness; it is a fact of consciousness and that is its primary mode of function, witnessing or seeing the world (Karika, 19).6 It is inherent in this primary function of the purusa that by so functioning it appears different from what it is; it appears as if it were a panorama of appearances, and appearances likewise appear as if they were possessed of consciousness. That is how a double obfusciation afflicts the basic human situation, namely concerning its awareness of the world and of himself (Karika, 20).7

The purusa appears as it is not and the prakriti appears other than itself. This double negation occurs because of the very nature of the purusa which has its function as witness and to reflect or to appear as it is not. In order to be what it is, it must appear as what it is not.

It is to the implication of this doctrine that Bhai Nand Lal Goya, a contemporary and beloved disciple of the Tenth Nanak, Guru Gobind Singh, refers in his Persian poem:

We understand not that, from the begining of Time, the human consciousness constitutes the instrumenatlity through which the Maker of appearances builds a mansion for Himself.8

It follows that between purusa and the process of purusartha "for the sake of purusa" no consciousness, deity or mind functions in the genesis of the manifest world. In its own nature and by itself the world is simply avyakta (un-manifest) as long as it is not in the vicinity of the purusa. The ultimate avyakta, mulaprakriti, is a confection of three gunas, but these gunas do not become creative unless in the presence of the purusa. In the primal state, the avyakta potentially contains everything that is in the un-manifest world, but in, and of, itself it is just an unconditioned, un-manifest, plentitude of being which is completely and utterly unconscious (Karika, 11).9

The manifest world begins to emerge or unfold when purusa comes into the proximity of this avyakta, the plentitude of the un-manifest being. The gunas, three in number (triguna) in admixture with the mulaprikriti, gives rise to a series of evolutes or emergents from which is created the world of appearances. These gunas extend through the avyakta and vyakta and they are continually modified and transformed in the proximity of the purusa. They constitute the psychophysical make-up of human nature and they likewise constitute the nature of everything non-human and inorganic, and thus, they represent the fundamental structure of both the worlds, the seen and the un-seen. In themselves, however, they are wholly and utterly unconscious and like the mulaprakriti they are absolutely separate from the purusa (Karika, 14).10

Thus in the Samkhya philosophy, the fundamental categories recognize no consciousness, or absolute or a Creator God. It does not deny the existence of gods, or even a God, the only and the lonely God. The God or the gods, indeed, may exist but they can be no more than the products of interaction of unconscious mulaprakriti and the conscious purusa, and the unconscious gunas.

This dualism of Samkhya focuses on the distinction of the conscious and the unconscious, that between individual consciousness as one term and the unconsciousness as the other term. It is not the dualism of "mind" and "body" and "thought" and "extension" which are regarded as different dimensions or attributes of the world of appearances and their unity is supported by the doctrine of gunas.

The purusa, the essence of which is consciousness is not a part of the manifest world which is unconsciousness. The purusa should not be confused with buddhi, the intellect, ahamkara, the I-consciousness, or manas, the mind. The content of this purusa can only be what it is not.

The Tantrayana or Vajrayana school of Buddhism, founded in fourth century by Arya Asanga, adopted this insight as the base of the doctrine of Sunyata, the basic emptiness that sustains the human situation, the world and man's awareness of it, dridham saramasausiryam achhedya abhedya laksnam adahi avinasi ca sunyata vajra mucayate (Sunyata is designated as vajra, because it is firm, sound, cannot be penetrated, cannot be burnt and cannot be destroyed).

It is this insight on which is based the poetic imagery of the ancient text of Samkhya-Karika which says: "After showing her face to the purusa the prakriti disappears like a dancer after her enchanting performance on the stage." "This is my considered view that there is nothing more sensitive and shy than prakriti who, once she knows that she has been seen by the purusa, never again unveils her bewitching face to the purusa."11