Lost in Partition, the Sikh-Muslim connection comes alive in the tale of Guru Nanak and Bhai Mardana

A descendant of the guru’s Muslim disciple speaks of the importance of the rubabi tradition in Sikhism.

“Why weren’t the Muslim rubabi protected? They held such high status in Sikhism? Why were they allowed to leave East Punjab at the time of Partition?” I asked.

The question was directed at Ghulam Hussain. I was in his home, deep within the older part of Lahore, close to the shrine of Data Darbar, the city’s patron saint. Dressed in a white shalwar kameez and maroon waist coat, a white scarf tied around his neck, the octogenarian had only recently recovered from what had become for him a recurring sickness. He had nevertheless agreed to my request for an interview. Behind him, the walls and cupboard were adorned with symbols of the Sikh religion – a picture of a kirpan, the Golden Temple – and numerous awards he had received from Sikh organisations over the years. Along with them were a few Islamic symbols, including a poster with a verse from the Quran. It was February of 2014 when I met Hussain. He died in April the following year, and this was possibly his last interview.

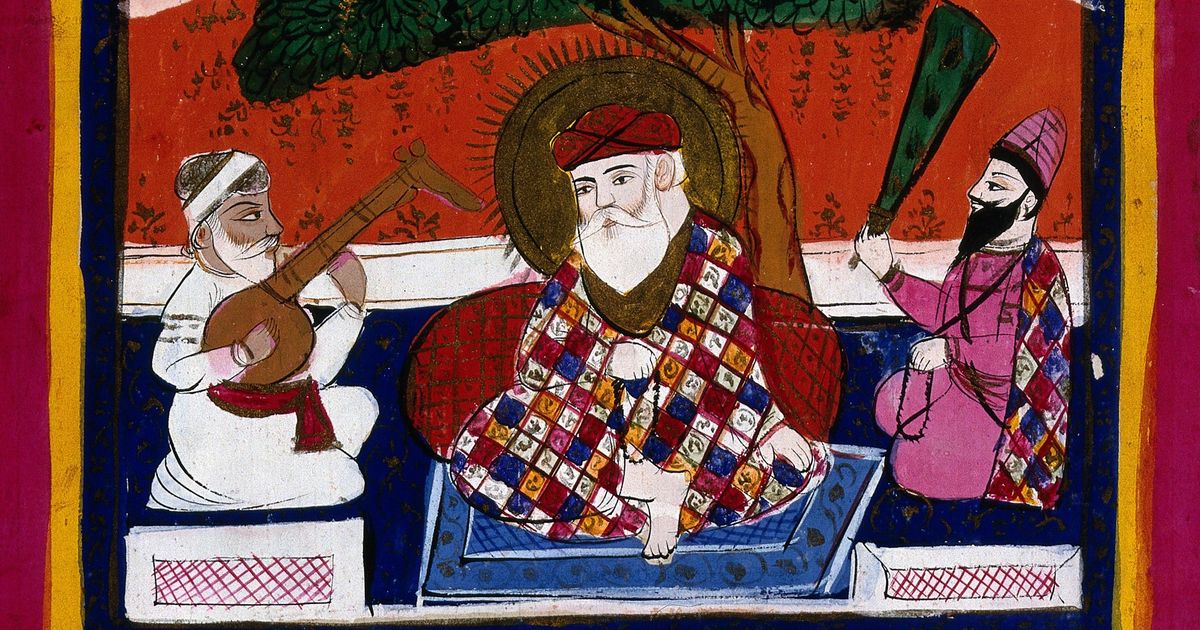

I had searched for Ghulam Hussain for a few years, having heard that he was a descendant of Bhai Mardana, Guru Nanak’s Muslim rubabi. Bhai Mardana played an important role in the development of the Sikh religion. Not only did he accompany Guru Nanak on his travels, he also played the rubab while Nanak sang his divinely inspired poetry. Since their time, Muslim rubabi had been given the responsibility of performing the kirtan at gurdwaras – till the tradition was abruptly disrupted during Partition.

From kirtan to qawwali

‘“Everyone was only concerned about their own selves at the time,” Hussain recalled. “We were Muslims, therefore we had to leave. It did not matter if we were rubabi. What mattered was our Muslim identity. That became our only identity. In fact, a couple of our rubabi even lost their lives during the riots. My father-in-law, Bhai Moti, was one of them. He used to play tabla at a gurdwara in Patiala. Another rubabi who used to perform at Guru Amardas’ gurdwara at Goindwal was also killed.”

He continued, “My chacha, Bhai Chand, was a rubabi at the Golden Temple. He had three houses in Amritsar, all of which were three storeys high. He was a millionaire at that time. He used to live in Bhaiyyon ki gali, named after the rubabi family. He became a pauper in Pakistan.”

Elaborating on his Sikh heritage, Hussain said his family’s ancestral gurdwara was Siyachal Sahib, which lies between Lahore and Amritsar. His father was a gyani – one who leads the congregation in prayer – who also gave lectures on Sikhism. “My father was the gadi nasheen of the rubabi seat there, which meant I would have taken over his position eventually,” he added.

But Partition changed all that. “Not only did we lose our money, we also lost our profession,” Hussain said. “While we knew the [Guru] Granth by heart, we knew nothing about being Muslim, besides the kalma. The Muslims had no interest in our profession. Thus, we began doing odd jobs – selling samosa, kheer, meat.”

However, Hussain soon found a second calling in qawwali, after receiving an invitation to a baithak by the Nizami Art Society. It was part of a weekly gathering of poets who recited and sang the works of Punjabi poets such as Bhai Gurdas, Shah Hussain and Bulleh Shah. “At one of these meetings, not many years after Partition, I was invited to perform qawwali,” Hussain said. “In those early days, I struggled because my Urdu pronunciation was weak. I couldn’t even read the script, having been trained in Gurmukhi. However, I practised and gradually mastered singing in Urdu. My financial condition also began improving.”

I asked him, “How similar or different are these two traditions, of kirtan and qawwali?”

He answered, “There is an old Punjabi saying – a hundred wise men sitting together will end up saying the same thing, while in a group of a hundred fools each one will say a different thing. Bulleh Shah reiterated what Nanak said. Guru Arjan’s and Sultan Bahu’s message is the same as that of Shah Hussain. Their kalam overlaps. In fact, I would go to the extent of saying that Guru Nanak expounded the Quran. Thus, to answer your question, qawwali and kirtan are part of the same tradition.”

A dying connection

But not everyone shares his view of syncretism.

Hussain’s son, sitting quietly with us as the interview progressed, suddenly jumped into the conversation. “A few Sikhs say Mardana was nothing but a funny character in Nanak’s Janamsakhis, who was always either hungry or thirsty,” he said. “I would choose to disagree. It was Mardana who brought out the divinity of Nanak. It was for Mardana that Nanak turned sweet the bitter fruit of a Kekkar tree.”

Hussain had a personal story of his own about Mardana’s importance in the history of Sikhism. “Once, before Partition, my father was at Gurdwara Panja Sahib in Hassanabdal,” he said. “He was in the sacred pool taking dips when one Sikh got offended and complained to the office. He accused my father of polluting the water. My father was summoned to the office. When questioned why he had taken a dip in the water, he asked the official, ‘Who did Nanak create this pool for? To quench Mardana’s thirst. This is, therefore, Mardana’s pool and I being a rubabi am his descendant. Now let me ask this question, who are you to claim ownership over this pool?’”

He let out a loud chuckle at the end of this story, but quickly became serious as he spoke of his visit to India and to the Golden Temple in 2005 – for the first time after Partition. “I wanted to perform at the Golden Temple,” he said. “My family had performed there for seven generations. We are the descendants of Bhai Sadha and Madha, who were appointed at the Golden Temple by Guru Tegh Bahadur. Such was our honour that we used to receive a share from the offerings at the shrine, which was then equally distributed among all the rubabi families. Throughout Sikh history, the rubabis have displayed their loyalty to the gurus. It was Bhai Bavak, a rubabi with Guru Hargobind, who rescued his daughter, Bibi Veera, from the Turks, when no other Sikh dared cross into their territory.”

But Hussain’s wish to perform at the gurdwara was not to be fulfilled. “Our family has a deep connection with the Golden Temple but now it has become extremely difficult for a rubabi to perform kirtan there. The officials there told me only Amritdhari could perform there,” he said, referring to Sikhs who have been initiated or baptised by taking amrit or “nectar water”.

He added, “I wanted to tell those officials that my ancestors had been performing kirtan here before Gobind Rai became Guru Gobind Singh. There is no tradition of any rubabi ever converting out of Islam. When the gurus never asked us to become Sikhs, then what right did these officials have?”

Lost in Partition, the Sikh-Muslim connection comes alive in the tale of Guru Nanak and Bhai Mardana

A descendant of the guru’s Muslim disciple speaks of the importance of the rubabi tradition in Sikhism.

“Why weren’t the Muslim rubabi protected? They held such high status in Sikhism? Why were they allowed to leave East Punjab at the time of Partition?” I asked.

The question was directed at Ghulam Hussain. I was in his home, deep within the older part of Lahore, close to the shrine of Data Darbar, the city’s patron saint. Dressed in a white shalwar kameez and maroon waist coat, a white scarf tied around his neck, the octogenarian had only recently recovered from what had become for him a recurring sickness. He had nevertheless agreed to my request for an interview. Behind him, the walls and cupboard were adorned with symbols of the Sikh religion – a picture of a kirpan, the Golden Temple – and numerous awards he had received from Sikh organisations over the years. Along with them were a few Islamic symbols, including a poster with a verse from the Quran. It was February of 2014 when I met Hussain. He died in April the following year, and this was possibly his last interview.

I had searched for Ghulam Hussain for a few years, having heard that he was a descendant of Bhai Mardana, Guru Nanak’s Muslim rubabi. Bhai Mardana played an important role in the development of the Sikh religion. Not only did he accompany Guru Nanak on his travels, he also played the rubab while Nanak sang his divinely inspired poetry. Since their time, Muslim rubabi had been given the responsibility of performing the kirtan at gurdwaras – till the tradition was abruptly disrupted during Partition.

From kirtan to qawwali

‘“Everyone was only concerned about their own selves at the time,” Hussain recalled. “We were Muslims, therefore we had to leave. It did not matter if we were rubabi. What mattered was our Muslim identity. That became our only identity. In fact, a couple of our rubabi even lost their lives during the riots. My father-in-law, Bhai Moti, was one of them. He used to play tabla at a gurdwara in Patiala. Another rubabi who used to perform at Guru Amardas’ gurdwara at Goindwal was also killed.”

He continued, “My chacha, Bhai Chand, was a rubabi at the Golden Temple. He had three houses in Amritsar, all of which were three storeys high. He was a millionaire at that time. He used to live in Bhaiyyon ki gali, named after the rubabi family. He became a pauper in Pakistan.”

Elaborating on his Sikh heritage, Hussain said his family’s ancestral gurdwara was Siyachal Sahib, which lies between Lahore and Amritsar. His father was a gyani – one who leads the congregation in prayer – who also gave lectures on Sikhism. “My father was the gadi nasheen of the rubabi seat there, which meant I would have taken over his position eventually,” he added.

But Partition changed all that. “Not only did we lose our money, we also lost our profession,” Hussain said. “While we knew the [Guru] Granth by heart, we knew nothing about being Muslim, besides the kalma. The Muslims had no interest in our profession. Thus, we began doing odd jobs – selling samosa, kheer, meat.”

However, Hussain soon found a second calling in qawwali, after receiving an invitation to a baithak by the Nizami Art Society. It was part of a weekly gathering of poets who recited and sang the works of Punjabi poets such as Bhai Gurdas, Shah Hussain and Bulleh Shah. “At one of these meetings, not many years after Partition, I was invited to perform qawwali,” Hussain said. “In those early days, I struggled because my Urdu pronunciation was weak. I couldn’t even read the script, having been trained in Gurmukhi. However, I practised and gradually mastered singing in Urdu. My financial condition also began improving.”

I asked him, “How similar or different are these two traditions, of kirtan and qawwali?”

He answered, “There is an old Punjabi saying – a hundred wise men sitting together will end up saying the same thing, while in a group of a hundred fools each one will say a different thing. Bulleh Shah reiterated what Nanak said. Guru Arjan’s and Sultan Bahu’s message is the same as that of Shah Hussain. Their kalam overlaps. In fact, I would go to the extent of saying that Guru Nanak expounded the Quran. Thus, to answer your question, qawwali and kirtan are part of the same tradition.”

A dying connection

But not everyone shares his view of syncretism.

Hussain’s son, sitting quietly with us as the interview progressed, suddenly jumped into the conversation. “A few Sikhs say Mardana was nothing but a funny character in Nanak’s Janamsakhis, who was always either hungry or thirsty,” he said. “I would choose to disagree. It was Mardana who brought out the divinity of Nanak. It was for Mardana that Nanak turned sweet the bitter fruit of a Kekkar tree.”

Hussain had a personal story of his own about Mardana’s importance in the history of Sikhism. “Once, before Partition, my father was at Gurdwara Panja Sahib in Hassanabdal,” he said. “He was in the sacred pool taking dips when one Sikh got offended and complained to the office. He accused my father of polluting the water. My father was summoned to the office. When questioned why he had taken a dip in the water, he asked the official, ‘Who did Nanak create this pool for? To quench Mardana’s thirst. This is, therefore, Mardana’s pool and I being a rubabi am his descendant. Now let me ask this question, who are you to claim ownership over this pool?’”

He let out a loud chuckle at the end of this story, but quickly became serious as he spoke of his visit to India and to the Golden Temple in 2005 – for the first time after Partition. “I wanted to perform at the Golden Temple,” he said. “My family had performed there for seven generations. We are the descendants of Bhai Sadha and Madha, who were appointed at the Golden Temple by Guru Tegh Bahadur. Such was our honour that we used to receive a share from the offerings at the shrine, which was then equally distributed among all the rubabi families. Throughout Sikh history, the rubabis have displayed their loyalty to the gurus. It was Bhai Bavak, a rubabi with Guru Hargobind, who rescued his daughter, Bibi Veera, from the Turks, when no other Sikh dared cross into their territory.”

But Hussain’s wish to perform at the gurdwara was not to be fulfilled. “Our family has a deep connection with the Golden Temple but now it has become extremely difficult for a rubabi to perform kirtan there. The officials there told me only Amritdhari could perform there,” he said, referring to Sikhs who have been initiated or baptised by taking amrit or “nectar water”.

He added, “I wanted to tell those officials that my ancestors had been performing kirtan here before Gobind Rai became Guru Gobind Singh. There is no tradition of any rubabi ever converting out of Islam. When the gurus never asked us to become Sikhs, then what right did these officials have?”

Lost in Partition, the Sikh-Muslim connection comes alive in the tale of Guru Nanak and Bhai Mardana