The Gandhian path was focused only on the transfer of political power. However, Bhagat Singh’s vision was to transform independent India into a socialist and an egalitarian society...

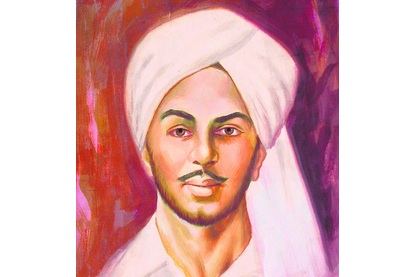

WHEN Mahatma Gandhi's statue was unveiled in London's Parliament Square on March 14, I started dreaming whether Bhagat Singh's statue would also be installed there one day. For the British establishment, Gandhi and Bhagat Singh are representatives of two contrasting world views and ideologies. They hanged Bhagat Singh but transferred political power to Gandhi's Congress party.

Divergent paths

The paths Gandhi and Bhagat Singh followed in their struggle against British rule were both competitive as well as complementary. Their paths were complementary because Bhagat Singh's martyrdom expanded the national base for the Independence struggle which in turn strengthened Gandhi's bargaining power with the British while Mahatma Gandhi's country-wide support base ensured greater popularity for Bhagat Singh. However, there was also intense competitiveness between the two paths that is rarely recognised in the narratives on India's Independence movement.

The Gandhian path was focussed on only the transfer of political power but Bhagat Singh's vision was to transform independent India into a socialist and egalitarian society. In the hanging of Bhagat Singh and his associates in March 1931, we lost an alternative socialist framework of governance for post-Independence India. The British rulers were acutely aware of the socialist perspective of the revolutionaries. Justice Medilton, who transported Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt for life in the Assembly Bomb Case, wrote in his judgement: “These persons used to enter the court with the cries of ‘Long Live Revolution’ and ‘Long Live Proletariat’ which shows clearly what sort of political ideology they cherish. In order to put a check in propagating these ideas I transport them for life”.

Bhagat Singh had read Karl Marx’s Das Capital and the works of other leading socialist thinkers. At his insistence, the name of Hindustan Republican Association was changed to Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. Jitendra Nath Sanyal, a co-prisoner in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, wrote in 1931:

“Bhagat Singh was an extremely well-read man and his special sphere of study was socialism… very few in India could be compared to him in the knowledge of this special subject” (cited by S Irfan Habib, To Make the Deaf Hear: Ideology and Programme of Bhagat Singh and His Comrades, p. 112).

By the time Bhagat Singh was hanged in 1931, he had risen in political stature to a level which was higher than all political leaders in India except, perhaps, Mahatma Gandhi. The evidence indicates that Bhagat Singh was equal in stature and political popularity to Gandhi almost everywhere in the country but certainly higher than him in Punjab. Nehru recognised that when he wrote: “He became a symbol and within a few months each town and village of the Punjab, and to a lesser extent in the rest of northern India, resounded with his name.

Innumerable songs grew about him and the popularity that the man achieved was something amazing (An Autobiography 1956: 174-75). Bhagat Singh Day was observed throughout Punjab on February 17, 1931. The Bhagat Singh Appeal Committees to campaign against the colonial authorities' decision to sentence him to death were set up in Kasur, Moga, Ferozepore, Sialkot, Ludhiana, Lyallpur, Phagwara, Banga, Batala, Montgomery, Gujaranwala, Amritsar and Sheikhupura. In my research, I found that in states as different as Assam and Andhra Pradesh, there are folk songs and rural craft works celebrating his bravery.

Soaring popularity

Three days after the hanging of Bhagat Singh, at the Karachi Session of the Congress, the mood in the country was one of anger against Gandhi for not opposing the hanging of Bhagat Singh. When Gandhi arrived to attend the Session, a black flag demonstration by angry youth shouted slogans: “Down with Gandhi”. Subhas Bose captured the moment: “Bhagat Singh had become the symbol of the new awakening among the youths...”. The Director of Intelligence Bureau Horace Williamson noted, “His photograph was on sale in every city and township and for a time rivalled in popularity even that of Mr. Gandhi himself”.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, there were two serious ideological contenders for leadership of India's national movement: Gandhi and Bhagat Singh. Gandhism was a perspective of minimal socio-economic transformation as a replacement of British imperial rule. It was focused on transfer of political power.

Gandhi was even willing to accept a subordinate dominion status for India under the broad structure of imperial rule. His compromising role vis-à-vis British imperialism faced sharp criticism from Subhas Bose and in muted voices even from Nehru. A part of the reason for his compromising stance towards British imperialism was the serious involvement of the top layers of India's capitalist class (Birla, Purushottamdas Thakurdass, and Walchand Hirachand etc.) in the influencing, if not the making, of the Gandhian perspective. It is not surprising now that leading business houses that include Infosys co-founder N R Narayana Murthy, Bajaj auto chief industrialist Rahul Bajaj and steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal have made generous contributions to the funding of the Gandhi statue in London.

A major weakness of Gandhi, which endeared him to the capitalist class, was that Gandhi did not have any understanding of the political economy or of the exploitative nature of capitalism and imperialism. Yusuf Meherali, a socialist, had once mockingly remarked that imperialism cannot be overthrown through a “change of heart,” as Gandhi seemed to believe.

Impact of Hinduism

Gandhi's strength was in understanding the deep impact of Hinduism on the consciousness of the majority Hindu population. This led him to coin slogans such as “Ram Rajya” and to invoke the ideas of gau-raksha, varnashram dharma and brahmacharya, which resonated with the vast majority of the Hindu population, especially the upper-caste segments.

In this strength also lay his weakness. It was his alienation of Muslims which resulted eventually in the creation of Pakistan, and he never had any influence, whatsoever, amongst the Sikhs after his arrogant characterisation of Guru Gobind Singh as a misguided leader. It is doubtful if he had any serious influence amongst the Christians. Proximity to Hinduism allowed Gandhi to feel the pulse of India's majority but that also resulted in an over-all conservative orientation to his ideas, perspectives and actions.

In contrast, Bhagat Singh and his comrades were strong in understanding the logic of the world capitalist economy and the class structure of colonialism but were weak in building an organisational structure in comparison with Gandhi's Congress party. Had Bhagat Singh not been hanged in 1931, there would have been a serious contest between the Gandhi-led Congress vision and the Bhagat Singh-led socialist vision. Bhagat Singh also had the advantage over the Indian communists that his radicalism was popularly seen as home grown and rooted.

Rallying force

With Bhagat Singh in the leadership position of the Indian socialist tradition, he would have become the rallying force against the Gandhi-led Congress's pro-capitalist vision. It is worth imagining that the polarisations in the country would not have been Congress vs Muslim League, Hindu vs Muslim and Gandhi vs Jinnah but would have been Gandhi vs Bhagat Singh, capitalism vs socialism and mere transfer of power vs socio-economic revolution.

In situations of intense political struggles, the relative positions of competing organisations and ideologies can undergo rapid change as it happened in Russia in 1917. Of the many possibilities open in the 1930s in India, one was a large-scale migration of the Congress cadre to the fold of the Bhagat Singh-led radical alternative. That possibility died with the hanging of Bhagat Singh.

Individuals do not make history but key individuals at critical moments do matter in making history. Gandhi and the colonial authorities understood the critical historical importance of Bhagat Singh. The Gandhi- Irwin Pact of 1931 between Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Irwin stipulated the suspension of the Civil Disobedience movement by the Congress party in return for the release of political prisoners. Gandhi did not insist on either the release of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru or even on the commutation of their death sentence to life imprisonment.

Cultural trade-off

This decision of Gandhi was not simply the result of the moralist/pacifist Gandhi not endorsing violence because by allowing hanging he was endorsing another kind of violence; it was the result of an extremely sharp tactician and strategist Gandhi realising that if Bhagat Singh survived, an alternative to his (Gandhi's) political leadership of India's Independence movement was a distinct possibility. For the colonial authorities, the survival of Bhagat Singh could have meant facing a revolutionary movement against them in competition with the ever-compromising Gandhi-led Congress movement.

The installation of the new Gandhi statue by the current British government may be considered, on a short-term and immediate basis, as a cultural trade-off for the commercial gain of being awarded the contract for massive armament sale to India but, on a long-term basis, it represents a recognition on the part of the British state that Gandhism prevented the possibility of a more radical overthrow of the weak British empire after the end of

World War II.

Therefore, there would not be a Bhagat Singh statue in London's Parliament Square in the foreseeable future.

That does not, however, stop us from dreaming of one.

Pritam Singh

— The writer is Professor of Economics at

Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK

Reference: Bhagat Singh, Gandhi and the British

WHEN Mahatma Gandhi's statue was unveiled in London's Parliament Square on March 14, I started dreaming whether Bhagat Singh's statue would also be installed there one day. For the British establishment, Gandhi and Bhagat Singh are representatives of two contrasting world views and ideologies. They hanged Bhagat Singh but transferred political power to Gandhi's Congress party.

Divergent paths

The paths Gandhi and Bhagat Singh followed in their struggle against British rule were both competitive as well as complementary. Their paths were complementary because Bhagat Singh's martyrdom expanded the national base for the Independence struggle which in turn strengthened Gandhi's bargaining power with the British while Mahatma Gandhi's country-wide support base ensured greater popularity for Bhagat Singh. However, there was also intense competitiveness between the two paths that is rarely recognised in the narratives on India's Independence movement.

The Gandhian path was focussed on only the transfer of political power but Bhagat Singh's vision was to transform independent India into a socialist and egalitarian society. In the hanging of Bhagat Singh and his associates in March 1931, we lost an alternative socialist framework of governance for post-Independence India. The British rulers were acutely aware of the socialist perspective of the revolutionaries. Justice Medilton, who transported Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt for life in the Assembly Bomb Case, wrote in his judgement: “These persons used to enter the court with the cries of ‘Long Live Revolution’ and ‘Long Live Proletariat’ which shows clearly what sort of political ideology they cherish. In order to put a check in propagating these ideas I transport them for life”.

Bhagat Singh had read Karl Marx’s Das Capital and the works of other leading socialist thinkers. At his insistence, the name of Hindustan Republican Association was changed to Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. Jitendra Nath Sanyal, a co-prisoner in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, wrote in 1931:

“Bhagat Singh was an extremely well-read man and his special sphere of study was socialism… very few in India could be compared to him in the knowledge of this special subject” (cited by S Irfan Habib, To Make the Deaf Hear: Ideology and Programme of Bhagat Singh and His Comrades, p. 112).

By the time Bhagat Singh was hanged in 1931, he had risen in political stature to a level which was higher than all political leaders in India except, perhaps, Mahatma Gandhi. The evidence indicates that Bhagat Singh was equal in stature and political popularity to Gandhi almost everywhere in the country but certainly higher than him in Punjab. Nehru recognised that when he wrote: “He became a symbol and within a few months each town and village of the Punjab, and to a lesser extent in the rest of northern India, resounded with his name.

Innumerable songs grew about him and the popularity that the man achieved was something amazing (An Autobiography 1956: 174-75). Bhagat Singh Day was observed throughout Punjab on February 17, 1931. The Bhagat Singh Appeal Committees to campaign against the colonial authorities' decision to sentence him to death were set up in Kasur, Moga, Ferozepore, Sialkot, Ludhiana, Lyallpur, Phagwara, Banga, Batala, Montgomery, Gujaranwala, Amritsar and Sheikhupura. In my research, I found that in states as different as Assam and Andhra Pradesh, there are folk songs and rural craft works celebrating his bravery.

Soaring popularity

Three days after the hanging of Bhagat Singh, at the Karachi Session of the Congress, the mood in the country was one of anger against Gandhi for not opposing the hanging of Bhagat Singh. When Gandhi arrived to attend the Session, a black flag demonstration by angry youth shouted slogans: “Down with Gandhi”. Subhas Bose captured the moment: “Bhagat Singh had become the symbol of the new awakening among the youths...”. The Director of Intelligence Bureau Horace Williamson noted, “His photograph was on sale in every city and township and for a time rivalled in popularity even that of Mr. Gandhi himself”.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, there were two serious ideological contenders for leadership of India's national movement: Gandhi and Bhagat Singh. Gandhism was a perspective of minimal socio-economic transformation as a replacement of British imperial rule. It was focused on transfer of political power.

Gandhi was even willing to accept a subordinate dominion status for India under the broad structure of imperial rule. His compromising role vis-à-vis British imperialism faced sharp criticism from Subhas Bose and in muted voices even from Nehru. A part of the reason for his compromising stance towards British imperialism was the serious involvement of the top layers of India's capitalist class (Birla, Purushottamdas Thakurdass, and Walchand Hirachand etc.) in the influencing, if not the making, of the Gandhian perspective. It is not surprising now that leading business houses that include Infosys co-founder N R Narayana Murthy, Bajaj auto chief industrialist Rahul Bajaj and steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal have made generous contributions to the funding of the Gandhi statue in London.

A major weakness of Gandhi, which endeared him to the capitalist class, was that Gandhi did not have any understanding of the political economy or of the exploitative nature of capitalism and imperialism. Yusuf Meherali, a socialist, had once mockingly remarked that imperialism cannot be overthrown through a “change of heart,” as Gandhi seemed to believe.

Impact of Hinduism

Gandhi's strength was in understanding the deep impact of Hinduism on the consciousness of the majority Hindu population. This led him to coin slogans such as “Ram Rajya” and to invoke the ideas of gau-raksha, varnashram dharma and brahmacharya, which resonated with the vast majority of the Hindu population, especially the upper-caste segments.

In this strength also lay his weakness. It was his alienation of Muslims which resulted eventually in the creation of Pakistan, and he never had any influence, whatsoever, amongst the Sikhs after his arrogant characterisation of Guru Gobind Singh as a misguided leader. It is doubtful if he had any serious influence amongst the Christians. Proximity to Hinduism allowed Gandhi to feel the pulse of India's majority but that also resulted in an over-all conservative orientation to his ideas, perspectives and actions.

In contrast, Bhagat Singh and his comrades were strong in understanding the logic of the world capitalist economy and the class structure of colonialism but were weak in building an organisational structure in comparison with Gandhi's Congress party. Had Bhagat Singh not been hanged in 1931, there would have been a serious contest between the Gandhi-led Congress vision and the Bhagat Singh-led socialist vision. Bhagat Singh also had the advantage over the Indian communists that his radicalism was popularly seen as home grown and rooted.

Rallying force

With Bhagat Singh in the leadership position of the Indian socialist tradition, he would have become the rallying force against the Gandhi-led Congress's pro-capitalist vision. It is worth imagining that the polarisations in the country would not have been Congress vs Muslim League, Hindu vs Muslim and Gandhi vs Jinnah but would have been Gandhi vs Bhagat Singh, capitalism vs socialism and mere transfer of power vs socio-economic revolution.

In situations of intense political struggles, the relative positions of competing organisations and ideologies can undergo rapid change as it happened in Russia in 1917. Of the many possibilities open in the 1930s in India, one was a large-scale migration of the Congress cadre to the fold of the Bhagat Singh-led radical alternative. That possibility died with the hanging of Bhagat Singh.

Individuals do not make history but key individuals at critical moments do matter in making history. Gandhi and the colonial authorities understood the critical historical importance of Bhagat Singh. The Gandhi- Irwin Pact of 1931 between Mahatma Gandhi and Lord Irwin stipulated the suspension of the Civil Disobedience movement by the Congress party in return for the release of political prisoners. Gandhi did not insist on either the release of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru or even on the commutation of their death sentence to life imprisonment.

Cultural trade-off

This decision of Gandhi was not simply the result of the moralist/pacifist Gandhi not endorsing violence because by allowing hanging he was endorsing another kind of violence; it was the result of an extremely sharp tactician and strategist Gandhi realising that if Bhagat Singh survived, an alternative to his (Gandhi's) political leadership of India's Independence movement was a distinct possibility. For the colonial authorities, the survival of Bhagat Singh could have meant facing a revolutionary movement against them in competition with the ever-compromising Gandhi-led Congress movement.

The installation of the new Gandhi statue by the current British government may be considered, on a short-term and immediate basis, as a cultural trade-off for the commercial gain of being awarded the contract for massive armament sale to India but, on a long-term basis, it represents a recognition on the part of the British state that Gandhism prevented the possibility of a more radical overthrow of the weak British empire after the end of

World War II.

Therefore, there would not be a Bhagat Singh statue in London's Parliament Square in the foreseeable future.

That does not, however, stop us from dreaming of one.

Pritam Singh

— The writer is Professor of Economics at

Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK

Reference: Bhagat Singh, Gandhi and the British